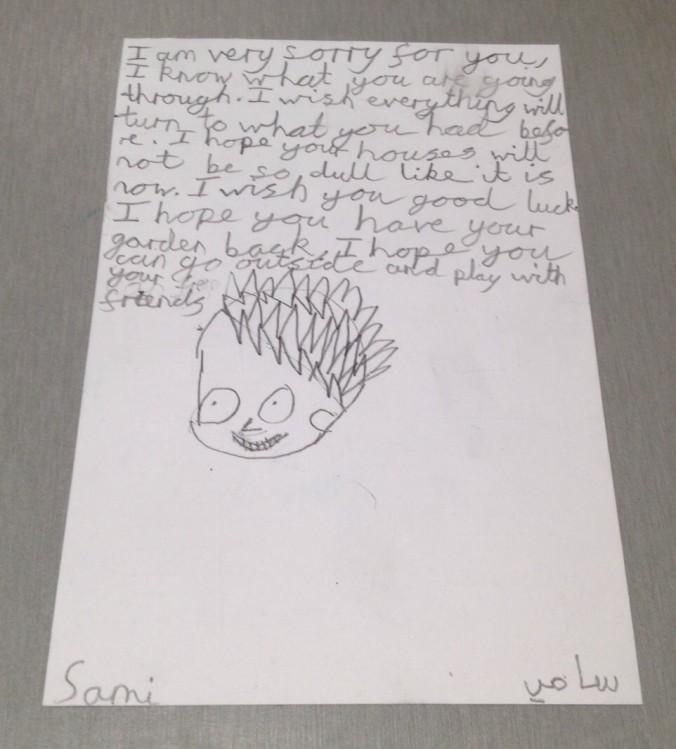

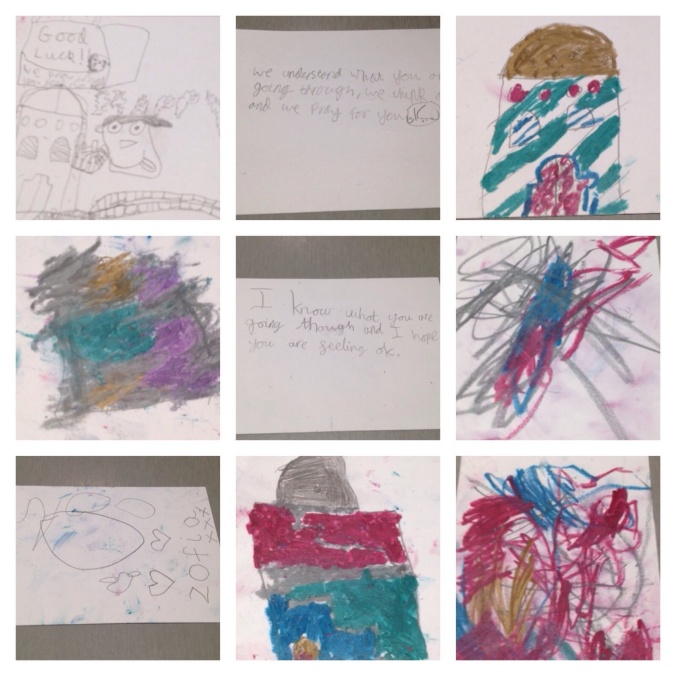

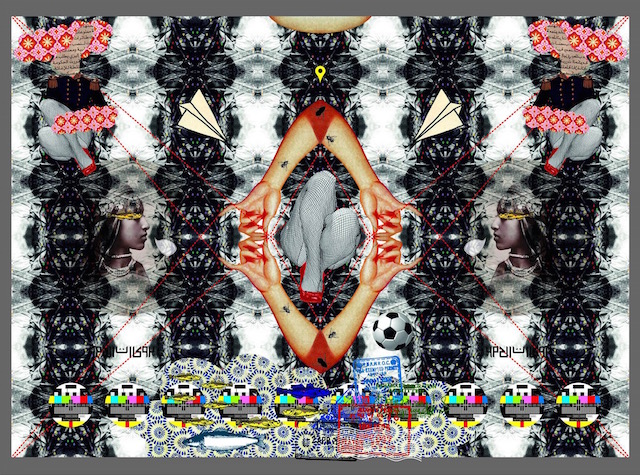

Stvdio El Sham :: MMX-MMXV is the first photographic exhibition showcasing the collaborative work between Lebanese photographer Tarek Moukaddem and Palestinian designer Omarivs Ioseph Filivs Dinæ. In this interview the artists talk to guest blogger Aimee Dawson about their exhibition and ongoing artistic collaboration.

Abu Saleh, The Official Portrait © Omarivs Ioseph Filivs Dinæ & Tarek Moukaddem

The three collections of works in your exhibition really show a process of development as each work inspires the next. They also show the story of your creative collaboration, which began in 2009, bringing together designer and photographer.

O: Each of the works has been shown in different formats at different venues internationally but this is the first time they have been shown altogether as framed photographic prints – as artworks if you will. And I think the relationship between photography and performance/pretence can be traced through each.

Can you say something about The Official Portrait – what was the inspiration behind this work?

O: The Official Portrait is the final production phase of The Ceremonial Vniform project, in which I set out to create an imaginary uniform for the imaginary Palestinian state. The project was a response to, and critique of, the Palestinian National Authority’s (PNA) 2011 bid for membership of the United Nations and the consequentl (defeatist) acceptance of the 1967 borders for the future State of Palestine.

The Palestinian authority is obsessed with creating symbols of Palestinian nationality and statehood at the expense of liberation and emancipation. The uniform in this work is the manifestation of this ridiculous compromise – all the same, it’s not a caricature. There is a parody to the work, there is something funny and cynical about it; however, it is not about emasculation or diminishing the actual men within the images. The design work and research are very serious, perhaps even more serious than the actual statehood bid which the PNA is so obsessed with – that is where the irony and mockery of the Palestinian political establishment lies.

Abu Zuhair, The Official Portrait © Omarivs Ioseph Filivs Dinæ and Tarek Moukaddem

Could you explain your process behind taking the images for Stvdio El Sham [MMXIII – MMIII]?

T: I consider Stvdio El Sham [MMXIII – MMIII] more of an ongoing experiment than a project. It came at a time when selfies were becoming very popular, and taking a picture of oneself has become very mundane and something that is too easy and quick to do. From my perspective as a photographer, I wanted to see if we could change the experiences of some people by putting them in a different context altogether. So we attempted to set up a photographic space that felt more like an old photographic studio set with an abundance of clothing and props to see how they might react differently and how they would present and represent themselves in such context. It was playful, about self-reflection and self-portrayal; how you see photography; and how you perceive yourself through photography if you have an altogether different concept of time and resources to do it.

O: In the past, our collaborative projects have been about me showing my work by seeking Tarek’s support as an accomplished photographer. In the Stvdio El Sham [MMX – MMXV] exhibition I wanted to show how the image making was really about both of us: both of our technical abilities combined to create images, as glimpses into an imagined reality. We are both very particular technicians who understand our mediums very well and know our own abilities and limitations. I consider myself a designer and never an artist. Indeed, it is almost insulting for me to be considered an artist as that reflects a vague notion of skill and understanding of one’s medium as opposed to design. Anyone could be an artist, but few could claim to be a painter, sculptor, draughtsman or photographer. All of these require a true mastery of design and a sensory understanding of material to begin with. Concepts are altogether irrelevant if they are not inherently supported by their material mediums. So many pseudo intellectuals writing and theorising, claiming to be conceptual artists are indeed nothing but ‘con-artists’!

Paper V, Silk Thread Martyrs © Omarivs Ioseph Filivs Dinæ and Tarek Moukaddem

Who were the people in the images and what was it like working with them? Was there a negotiation with them in creating the photos?

T: I know most of them but not all of them closely. We put out an open call inviting people to come to the studio and some of them were friends and some of them were random. It was very playful – we didn’t want to make too many rules but we wanted it to still have an old studio style. We had a lot of props and so they could make their own choices but they also asked us for our opinion. So it was more of a collaboration.

O: In the exhibition there is little information about the sitters beside the images. When you are trying to explain the person in the photo it defeats the purpose of the image-making. We want it to be about the image in and of itself, not literature or history.

Why did you choose to only photograph males in this latest work?

T: We were looking at gender issues and the way that the male is represented in Arab societies, and especially in our own societies; challenging the idea of the ‘macho’ stereotype. Most of my photography work focuses on the male body. I think there is a lot of focus on the female body of the ‘Orient’ and the issue of veiling and so on – there is comparatively little photography of men.

O: It is simply more honest or genuine, as two males, to photograph other males. It makes sense for us to represent bodies that are familiar and ‘phenomenologically’ relevant to us. We are not looking to represent anyone other than ourselves.

Joe, Stvdio El Sham [MMXIII – MMIII] © Omarivs Ioseph Filivs Dinæ and Tarek Moukaddem

O: I was in Beirut this summer researching and working on a project as part of my MA in Social Anthropology on Palestinian embroidery techniques with INAASH (Association for the Development of Palestinian Camps in Lebanon). The project is called Fifteen [XV] Stitches Embroidery Project. The aim is to identify and understand the techniques of different Palestinian Bedouin and peasant embroidery stitches and to try and push them further than the tedious and overrated cross-stitch, which is mere surface embroidery and ornamental. This was already done in Palestine with a great aunt of mine and in collaboration with Sunbula, an NGO based in Jerusalem in 2010. In Beirut I was, and will be in the near future, sharing these techniques with the Palestinian Refugee women embroiderers who work with INAASH.

Najaf IV, Silk Thread Martyrs © Omarivs Ioseph Filivs Dinæ and Tarek Moukaddem

I consider the cross-stitch the most superficial and mundane part of the rural Palestinian dress system – there’s a lot more which is functional and structural that reflects true design and the diversity of a complex society. My belief is that Palestinian dress, or Palestinian costume as it is widely known, has been reduced to ornamental embroidery by the Palestinian intelligentsia, artists and urban middle classes, who are anxious to justify the Palestinian cause on nationalist narratives and ideas of authenticity by creating symbols and images around which contemporary Palestinians can rally. All this, some serious and scholarly work on the subject by international and Palestinian researchers notwithstanding. I am more interested in design and functionality and how form is the product of technique influenced by local sensibilities and nuance – how such techniques are made and themselves actively make the individual.

Stvdio El Sham :: MMX-MMXV was on show at The Muse At 269 Gallery/Studio in London until 8 November, as part of Nour Festival of Arts 2015.