Meriem Bennani; the New York-based artist who was recently featured in the New York Times is one of the selected artists by Riffy Ahmed and Sarah El Hamed for the ARA-B-LESS? project at the Saatchi Gallery. Our guest blogger Aimee Dawson speaks with Riffy to learn more about the project.

How did you conceive the title ARA-B-LESS ?

The project title ‘ARA-B-LESS ?’ is a neologism born of a play on the word ‘Arabness’ (Arabism). Two designs hint at the meaning behind “ARA-B-LESS ?” – the first emphasising ‘BLESS’ suggests that Arab identity is a blessing, while the second emphasises “LESS’, the ways in which what it means to be Arab have evolved over time, perhaps losing something along the way. ‘ARA-B-LESS?’, as a question, also focuses on whether we, the artists, consider ourselves to be more or less Arab for having been born and brought up in the West, albeit by parents from Arab countries.

Can you describe the show a little? What does the performance description mean by three different ‘landscapes’?

The show integrates live performance art with video, sculpture and installation work. Operating in the interstices between reality and fiction and inspired by Grayson Perry’s Map of an Englishman, 2004, ARA-B-LESS? invites the audience to embark on a journey through three conceptually cohesive spaces each posing a unique challenge to current codes of conduct as well as questioning the existence of multifarious stereotypes and framing devices. The result is an extensive yet playful investigation of the ways in which identity is constructed as well as the ways in which it might be deconstructed and reconstructed in the realm of the hyper-real.

How do you think Arab women are perceived and represented? Are you looking at it from a ‘Western’ gaze or Middle Eastern/Arab or…?

How do you think Arab women are perceived and represented? Are you looking at it from a ‘Western’ gaze or Middle Eastern/Arab or…?

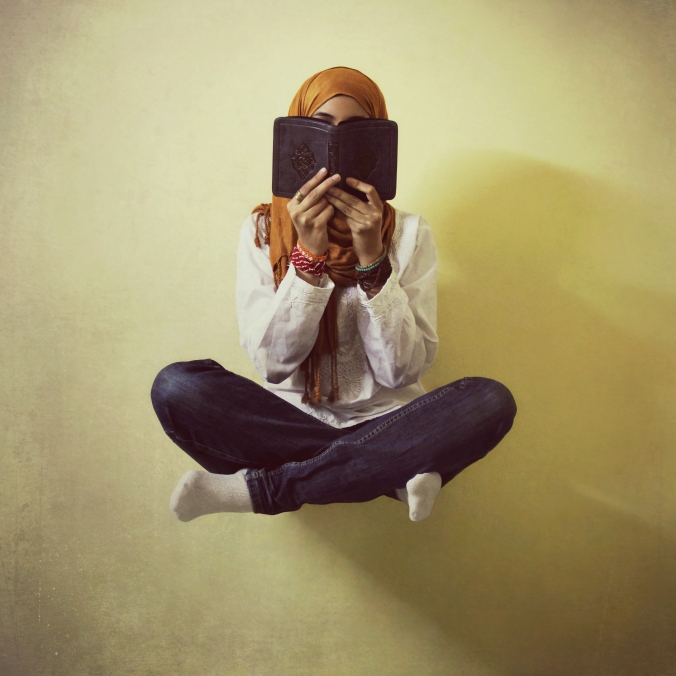

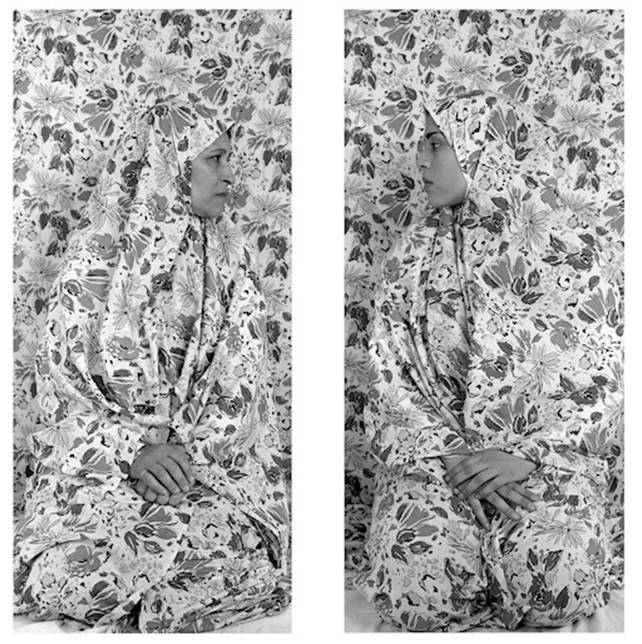

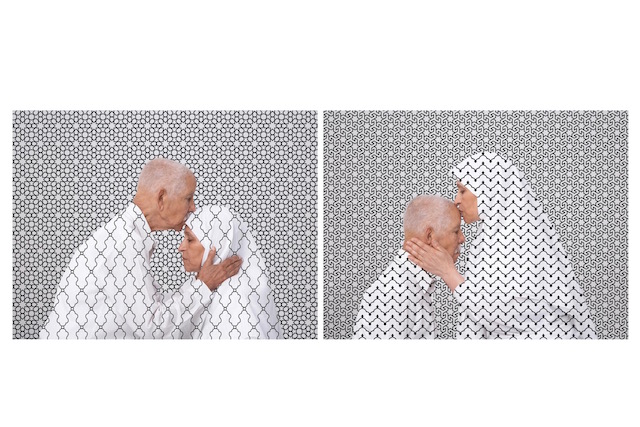

The short answer is both from a Western and a Middle Eastern/Arab gaze, there is no limit to the ways in which women’s identity might be interrogated in the work of each artist – the whole point is to explore and ask questions. ARA-B-LESS ?, designed in broad terms to explore notions of Arabness and more specifically to explore the representation of women in these different cultures, is an essentially collaborative project. The result is a series of ongoing conversations between artist-curators Riffy Ahmed and Sarah El Hamed. Together, they have selected works by artists who complement, counter, and complicate their thinking about the representation of identity.

How is the work interactive? What can people expect?

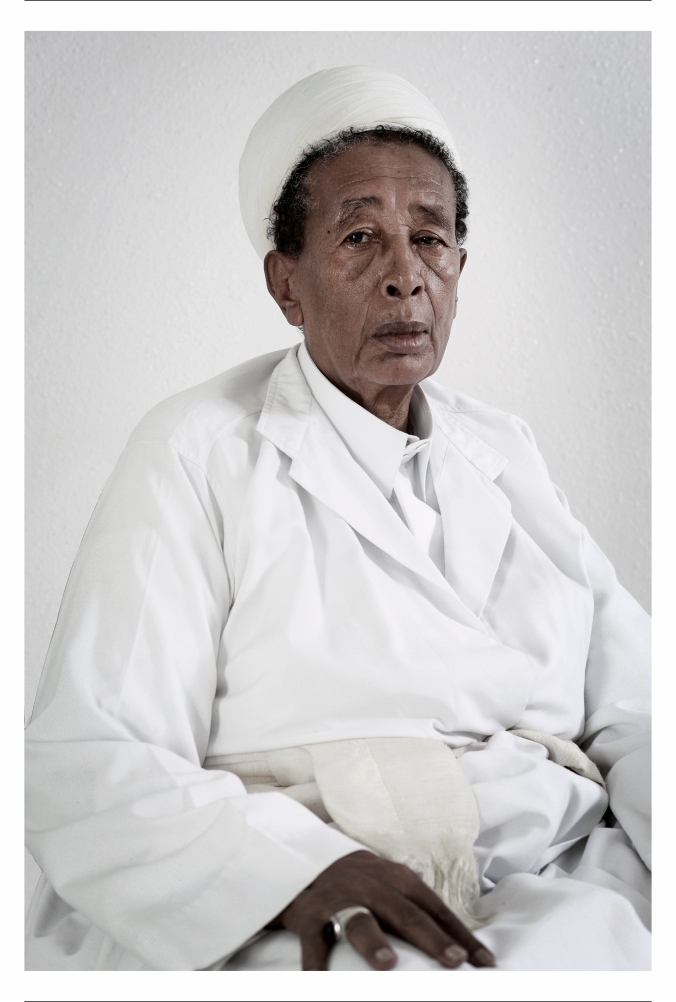

There will be three performances (each 10 minutes in length) by Ahmed and El Hamed (visitors will be informed and directed by staff before each is about to start) as well as a durational performance inspired by Hassan Hajjaj’s photographic portraits. The subject of this performance, who will pose throughout the evening in a Hajjaj constructed environment, will also wear clothes designed by the artist.

Visitors to Shadi Al Zaqzouq’s work will also be able to participate by purchasing or simply trying on his eccentric creations – hijabs adorned by colourful variations on the Liberty Spike Mohawk. There will also be live music throughout the evening courtesy of Algerian singer and guitarist, Nedjim Bouizzoul.

The ARA-B-LESS? performance takes place on Wednesday 4 November, 7pm at Saatchi Gallery, Duke of York’s Square.

To book tickets click here.